On the morning of November 9, 1975, a subtle shift began over the Great Plains. An area of low pressure, initially dismissed as another typical fall storm, was quietly gathering strength in Kansas. Few suspected this would become a day etched in maritime tragedy.

The S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald, a colossal freighter and “queen of the Great Lakes,” was loading over 24,000 tonnes of taconite pellets in Superior, Wisconsin. Her destination: Zug Island, near Detroit. For seventeen years, the Fitz had relentlessly traversed the lakes, completing 748 round trips – a distance equivalent to circling the globe forty-four times.

At 2:20 p.m., Captain Ernest McSorely, a seasoned veteran nearing retirement, guided the Fitzgerald onto the waters with his usual confidence. Twenty-nine crew members, each among the most skilled on the Great Lakes, prepared for what should have been a routine voyage. They had no idea it would be their last.

The story of the Fitzgerald is also the story of ambition and industry. Following World War II, a spirit of relentless progress swept the West. Edmund Fitzgerald, CEO of Northern Mutual Life Insurance, embodied this ethos. His company, heavily invested in iron mining, commissioned the construction of the largest ore carrier on the Great Lakes – a testament to American enterprise.

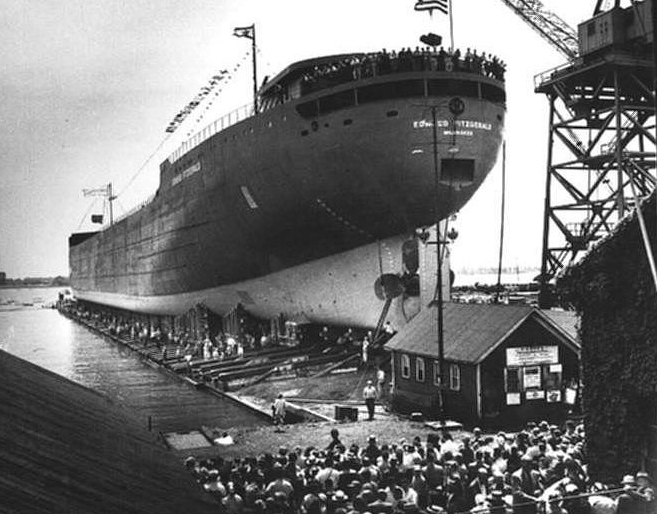

Launched in 1958, the Fitzgerald was a marvel of engineering, built by over 700 men along the Detroit River. The mechanical superintendent proudly declared, “We sure are proud of her.” More than 15,000 people gathered to witness her maiden voyage, captivated by the sheer scale and beauty of the vessel.

By the evening of November 9th, the seemingly harmless low-pressure system had intensified, rapidly moving towards Upper Michigan. The U.S. Weather Service would later report its “most rapid intensification” as it barreled towards Lake Superior. Winds began to howl, and waves swelled, foreshadowing the brutal conditions to come.

As the storm escalated, the Fitzgerald and another ship, the Arthur Anderson, altered course, seeking refuge along the Ontario shore. The Fitz reported winds reaching 160 km/h and waves exceeding three metres. But these were merely the opening salvos of a monstrous assault.

Visibility plummeted to zero as hurricane-force winds and driving snow descended upon Lake Superior. The Edmund Fitzgerald, a ship celebrated for its safety record, was now battling a force of nature unlike anything her crew had experienced.

At 7:00 p.m., a desperate radio exchange revealed the escalating crisis. Captain McSorely reported topside damage – a broken fence rail, lost vents, and a dangerous list. He requested the Anderson stay nearby until they reached Whitefish Bay. “I have a bad list,” the Fitz would later radio, “lost both radars. And am taking heavy seas over the deck. One of the worst seas I’ve ever been in.”

Despite a history of minor incidents – groundings and collisions – the Fitzgerald had always persevered. She was known as the “workhorse of the Great Lakes,” consistently breaking shipping records. But the relentless pounding of the waves, each exceeding ten metres in height, proved too much.

The final communication came at 7:10 p.m. “We are holding our own,” McSorely assured the Anderson. Those were his last words. Shortly after, the Fitzgerald vanished into a squall, disappearing from the Anderson’s radar. It never reappeared.

Between 7:20 and 7:30 p.m. on November 10, 1975, the S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald slipped beneath the icy waves of Lake Superior, taking all twenty-nine souls with her. The Arthur M. Anderson, battered but afloat, was left to deliver the devastating news and begin a futile search.

The desperate search yielded only heartache. The Edmund Fitzgerald became a legend, a haunting reminder of the power of nature and the fragility of life on the Great Lakes. A tragedy, forever remembered in the faces and names of those left behind.